During the height of the Third Reich, a visit from Adolf Hitler was considered a significant honor for hotels across Europe. These establishments would be adorned with Nazi flags and swastikas to welcome the Führer. However, which hotels did Hitler prefer, and did they all welcome him? In the 1930s, several grand hotels in Berlin were deemed suitable for the Nazi leader. Some of these hotels would later be destroyed under the relentless bombardment by Allied forces.

One notable hotel was The Excelsior, which opened in 1908. Located on Askanischen Platz, opposite Anhalter Bahnhof, it was one of the world's largest and most modern hotels. With 600 rooms, nine restaurants, and various amenities, including a butcher and a baker, it also boasted an underground tunnel connecting the hotel to the station. Guests could even purchase their train tickets directly at The Excelsior. It is believed that the Nazi Party initially chose The Excelsior to host Hitler on the eve of his rise to power. However, Curt Elschner, the hotel director and not a supporter of the Nazi movement, reportedly declined the honor. Consequently, the Nazi leadership selected The Kaiserhof instead.

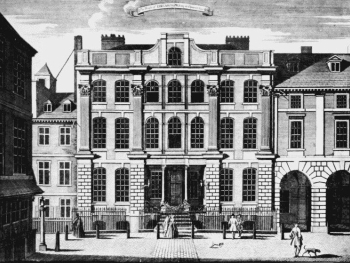

The Kaiserhof, a grand hotel on Berlin’s Wilhelmstrasse dating back to the 1870s, played a significant role in Germany’s pre-war history. It was at The Kaiserhof that the merger leading to the founding of Lufthansa was negotiated in 1926. In 1932, Nazi leaders used the hotel to plot Hitler's ascent to power, and in August of that year, Hitler himself moved into The Kaiserhof. The hotel also hosted significant events such as Göring's marriage celebration in 1935 and served as the official hotel for the 1936 Olympic Games. Like The Excelsior, The Kaiserhof was destroyed in the final days of the Third Reich.

Another prominent hotel was The Adlon on Unter den Linden. Before World War II, it was known as a hub for diplomats, earning the nickname 'Little Switzerland of Germany.' The Adlon was destroyed as Russian forces advanced into Berlin in 1945, but it has since been rebuilt and now operates as a Kempinski hotel, honoring its historic legacy.

In Munich, the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten (now a Kempinski hotel) on Maximilianstrasse was a meeting place for several far-right groups, including the pan-German Alldeutscher Verband, the antisemitic Hammerbund, and the Thule Society, whose emblem was a swastika. The hotel's owners, the Walterspiel brothers, were members of the Thule Society.

Elsewhere in Germany, Hitler favored the Deutscher Hof in Nürnberg, where he would occupy a large room on the first floor to watch the marching columns. The hotel even added a special Führer balcony in 1936. However, the Deutscher Hof has since closed. In Weimar, Hitler stayed at the Hotel Elephant on Marktplatz, where he would greet crowds and view marching columns from the entrance. In Berchtesgaden, near his mountain retreat on the Obersalzberg, he frequented the Hotel Zum Türken and the Hotel Platterhof.

In Vienna, Hitler's return to the city where he had once been a destitute laborer was marked by controversy. Despite his desire to stay at the luxurious Hotel Imperial, where he had once shoveled snow as a youth, the general manager Stefan Plank, an opponent of the Nazis, provided Hitler with a modest room. Plank, labeled a ‘friend of the Jews,’ was later imprisoned by the Nazi secret police.

On the southern coast of Gdansk Bay, the Grand Hotel in Sopot (then part of Danzig) was another venue Hitler frequented. In September 1939, after launching an artillery bombardment on Polish positions in Danzig, Hitler stayed at the Grand Hotel. From his suite, he watched as German warships destroyed the Polish fleet. Today, the hotel does not prominently advertise this part of its history, but acknowledging such past events is crucial to understanding and remembering the atrocities of that era.

These stories illustrate the complex and often dark history of the hotels that hosted one of history's most infamous figures. While some of these establishments have been rebuilt or repurposed, their histories serve as a reminder of a tumultuous past that should never be forgotten.